On love, labels, connection, connectivity and untold stories

Posted on March 10, 2025 in London

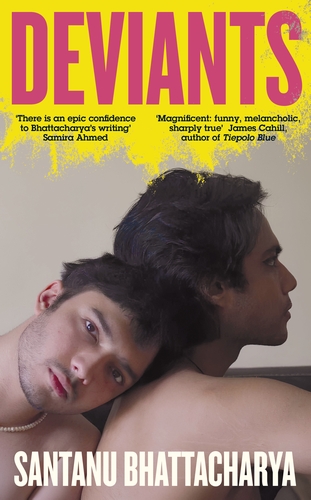

The bold neon pink characters scream the title on a neon yellow base. The book cover has every right to be loud, considering the unprecedented contents: the intergenerational story of three gay men from the same family in India. We hadn’t read anything like Deviants before. Not in Europe, and certainly not in India, where the section n. 377 of the penal code which criminalised homosexuality ruled until 2018.

Truth be told, the book cover that had been initially planned was much more sober, with a salmon pink edge and white characters, and a subtitle – The Queer Family Chronicles – that has been dropped in the current version. Not surprisingly, seeing how the author, Santanu Bhattacharya, believes in connection rather than exclusivity. ‘I wouldn’t market anything as “queer literature,” nor would I only speak to a queer readership,’ they declared in a recent interview.

The audience gathering at the Brixton library is a diverse bunch of younger and older people, with fluorescent hair colours but also grey heads, striped rainbows on nails and sweaters, long raincoats, denim jeans and trainers. If Deviants as a trailblazer is already making some noise, author Bhattacharya’s demeanour is all but loud, as they enter the conference room with a beaming smile on their face.

The audience is excited. ‘Sukumar [a character in the novel] was me!’ someone says out loud from the front row. Bhattacharya smiles at them, nodding.

Deviants comes out at a pivotal point in the lives of Indian people who identify as queer.

‘Ever since homosexuality was decriminalised seven years ago,’ Bhattacharya says, ‘the queer community has been growing away.’ So has the community’s accountability. India’s gen z is the first one to live post section 377. According to Bhattacharya, there’s a great deal of pressure that comes with being the ‘first of anything’: ‘As we open up as a community, certain questions arise: is this too conforming? Too straight? Or too queer?’

New labels don’t make life any easier: ‘After having been allowed to answer “yes” to “are you homosexual?” Now we need to answer: “Are you homoflexible? Are you heteroflexible?” It’s very confusing.’ Labels must be handled sensibly, Bhattacharya warns. Also, the struggle endured by the previous generations, who couldn’t even call themselves gay, or bisexual, should never be forgotten. This is the idea that prompted the intergenerational narration that is the backbone to the story.

‘UK is a country with so much recorded queer history, whilst in Southern Asia and India there’s none,’ explains Bhattacharya, ‘So, I thought, what can I do for the people who came before me, my ancestors?’ Essentially, Deviants was born out of the desire to tell the untold.

‘Besides, there hasn’t been a lot of fiction from India on an international scale, to look at the multi-generational progress, at the shifting of attitudes, which wouldn’t have been possible with one generation.’

The characters in the book have different voices, and their stories span over fifty years. Vivaan is a teenager, Mambro is Vivaan’s uncle and Sukumar is their grand-uncle. Vivaan talks to the reader through his voice, as he has the language and also the technology to express himself. Mambro, who is in his forties, is talking to his younger self, and so in the second singular person. But Sukumar’s story, who is the oldest, is told as a third person narrative.

‘Mambro is my generation, so he is processing his life in retrospect, now that the language and the media are available. Sukumar instead, is from a generation that wouldn’t have the language to tell us the story, that has to be told by somebody else.’

Ultimately, Bhattacharya explains, it’s not only the generation a character belongs to, but also their distinctive personality to determine the narrative. Sometimes the characters take over. It happened with Vivaan, for whom Bhattacharya had initially planned an entire chapter of grieving over a break up. ‘The thing is, Vivaan is a teenager, and as such he falls in and out of love very quickly. When I got to write the chapter, I heard Vivaan say “Fuck it, I can’t be arsed”. And I knew that was it. I had to find something else to write instead.’

Besides the pushing of boundaries and the experimenting with new labels, the youngest character in the novel is key in delivering another main theme: the importance of technology in shaping new relationships. ‘It can be very isolating and mess up with your brain,” says the author, ‘I don’t want to be a tech denier, because we all use technology, but it seems that the whole idea of finding a connection, of finding love, has completely moved online. I don’t know anyone who in the last few years has met in real life.’

Love, sexuality, relationships: at the onset of their writing career, Bhattacharya didn’t really want to work on themes so close to their own human experience. Their first novel, One Small Voice, an Observer debut novel in 2023, is a ‘fairly heterosexual story’ that took about ten years in the making. Bhattacharya’s debut happened in 2021, when they won a memoir competition that sparked a huge interest among publishers and literary agents. At that time the author had no intention of writing another memoir (‘I don’t like to make any claim of authenticity, I like the freedom given by fiction’) but times were not ripe yet for a story like Deviants. ‘I gave them [the publisher] One Small Voice because that was what I had available. But back then I wasn’t ready to come out as a writer, nor I think my family was ready for me to do so. And I’m glad that I waited, as the idea of an intergenerational story only came to me eventually.’

As the Q&A comes to a close, Bhattacharya emphasises two other gaps in Indian queer literature: there needs to be more writing in Indic languages, as not everyone can read English; and homosexuality needs a female perspective too. ‘There is an inherent privilege to the male existence from a social point of view. On the flip side, men had to face criminal conviction on the account of Section 377: what was criminalised was “unnatural sex” involving penetration. So women would not have the social privilege, but legally they had more cover. We need some female Indian writers to step up and tell their own stories.’

Listen to the podcast

Listen to the podcast  Explore the Youtube channel

Explore the Youtube channel